We decided that a 400km detour inland to cross from Tanzania into Mozambique would be better than strapping our car to three canoes and taking the river crossing across the border. There used to be a ferry, but it sank a few years ago and now the makeshift canoe option is offered by the local fishermen. The starting price apparently is a few hundred dollars, and what you actually pay depends on your negotiating skills!

The inland Unity Bridge is not without its issues either. It was built at a historical site and has huge tusks at the ends, but both countries forgot to build roads either side of it. At best there are pot holed dirt roads, so dusty that our car began to blend in to its surroundings. When the presidents flew in by helicopters for the official opening in 2010, they constructed 2km of tar road either side for the occasion. They were unaware apparently that the tar ended just beyond the helipads and road upgrading projects were then commissioned! On the Mozambique side, there is an unmarked dirt road that leads off from the tarmac. If you miss it, the tar leads into the bush a few hundred metres later. The road markings suggest that many people have made U-turns at this point back to the dirt track!

The border crossing is so infrequently used that the Mozambique immigration officer had to call the customs officer to come to work. “Sorry to keep you waiting,” he said when he arrived half an hour later. “I was sleeping.”

Northern Mozambique has recently opened up to tourism after a civil war that only ended in the early 1990s. The infrastructure is basic, but the coastline is beautiful and relatively untouched and there are some interesting places to visit. Geographically and culturally, it’s far removed from the capital and the south of the country, and there is still an Islamic influence here that dates back to the old Swahili trading routes. The coastline and islands are the big draw here and so our island hopping continued into Mozambique.

********************

We are learning a lot about tides. The dhow to Ibo island only sails at high tide and as we bumped along the dirt track we hoped we would make it in time. We still had to negotiate our parking spot which someone had written was ‘just next to the baobab tree by the bay where the boats leave from’.

Miraculously, it was just that. A compound next to the baobab tree where a few people had parked their 4x4s before catching a dhow to Ibo island. We could see a boat full of people a couple of hundred metres away, but getting to it involved wading waist deep (or chest deep in my case) through water to get to it. A bit of negotiating eventually got us a 10 year old boy and a leaky dugout to take us to the boat. More negotiating got us a passage to Ibo on a boat designed for 10, but that eventually carried close to 40 people, plus lots of belongings bundled up in brightly coloured fabric and a few fresh fish! The journey took an hour and it was fun trying out a few phrases of Portuguese with the locals as we huddled up to avoid the splashes of water.

No jetty in Ibo either so more wading to shore required and a damp walk through the streets to find a guest house.

“I can’t believe $90 doesn’t get you hot water!” This was a phrase I repeated a number of times whilst having a shower on the first chilly evening in Ibo. Over the next couple of days though, I began to appreciate the costs involved in having anything at all on this island – everything is brought over on boats from the mainland, including barrels of fuel for cooking and for the generators (electricity will only arrive in a few months), as well as all the food. Only fish is readily available locally.

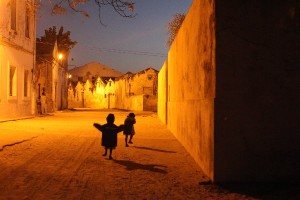

Ibo island feels like a place lost in time. Despite being able to walk around the tiny island in an hour, it was one of the largest towns in Mozambique in the late 18th century and central to the slave trade routes, especially in supplying the sugar plantations in Mauritius. Today its small population lives amongst the crumbling Portuguese colonial-era villas. The wide sandy ‘main street’ is disproportionate in size for the small number of people walking along it. There is a languid pace of life. Only the small children run around. This is in contrast to the adults who lounge around in the shade, sitting on the low walls of the verandahs whose roofs have long gone, and only the columns remain. These must have been grand villas in their day, but now trees have started to take over the buildings and push through the empty doorways and windows.

Ibo is also a quiet place. A man walks past with a length of rope in his hand and as we look round he has shimmied up a coconut tree to cut a few down. Occasionally you hear a talk show on a distant radio, and as you walk past the police station you hear the sound of a typewriter. It feels a bit like the Wild West.

A few of the buildings have been bought by foreigners and are being restored and converted into guest houses. They give glimpses of how the houses might have been many centuries ago.

Sunset is early, and at 4pm there’s already a trickle of tourists walking through the botanical garden to the fort to enjoy the big red African sun setting over the sandbanks and mangrove trees that have been left exposed at low tide.

We were lucky enough to be there at full moon. By 10pm, the generators have been switched off and all colour drained from the buildings. The moonlit black and white streets take on a subdued glow and the place feels very much like a ghost town.

********************

“When you get to Ilha de Mozambique, go to Barraca Sara,” we had been told. “It’s a restaurant in a shipping container and not in the guide books. It’s a local place without a sign, just ask around and you’ll find it.”

Sara was everything an African mama should be – smiling, friendly, and rotund, wearing a long printed dress and matching head scarf tied in a knot at the front. Best of all, her tiny reed-shack of a kitchen behind the shipping container produced the best grilled seafood we’ve had yet. The second night we went there, she welcomed us with a big smile and gave an extra big calamari and a prawn curry that had enough prawns to make up three dishes in any restaurant back home. Just when we thought we couldn’t eat any more, two plates of bananas cooked in a cardamon and peppercorn caramel arrived. Wow! And not forgetting that Mozambique has the best beer we’ve had in Africa so far – I hope they start exporting 2M soon…..

Ilha de Mozambique is only 3km by 500m, but has played a large role in the history of the region. It was already a boat building and trade centre in the 15th century, before Vasco da Gama arrived in 1498. Once a Portuguese settlement was established, it also became a naval base, and grew in importance to become the capital of Portuguese East Africa until it was moved to Maputo in the 19th century. It was also a melting pot of cultures with missionaries mixing with Muslims, Hindus and immigrants from other Portuguese colonies such as Goa and Macau as well as from other parts of East Africa. Quite impressive for such a small place. Today it’s predominantly Muslim and the local Makua culture, and we were glad to be at least a few blocks away from the bright green mosque that called to sunrise prayer at 4am!

For such a small place, there are still distinct areas. In the south is Makuti Town with its wooden houses tightly packed along narrow alleyways. Children and chickens run around whilst the mamas cook and do laundry which is then dried on the thatched roofs. Along the western shore you can watch the passenger dhows come in from the mainland or buy vegetables, bread and fish during the early morning chaos in the covered market.

The streets along the centre and across to the eastern shore are almost like a ghost town: rows of simple colonial era buildings with crumbling walls and flaking paint that hints at the reds, yellows and blues they were once covered in. Some of them are occupied and occasionally you can glimpse courtyard life amongst the rubble through an open doorway. There are also some grand buildings in disrepair: a huge hospital, a cinema, and an old sports club with some of the blue and white tiles that lined the walls of the bar still visible from the road.

The north of the island has a few imposing colonial-era buildings, including the restored former governor’s mansion and beautiful colonnaded walkways. There are also two structures worth remembering for trivia quizzes: the Fortaleza de Sao Sebastiao, which is the oldest complete standing fort in sub-Saharan Africa; and the Chapel of Nossa Senhora de Baluarte, the oldest European building in the southern hemisphere.

We loved walking the streets early in the morning before breakfast when there’s few people about and the light casts long shadows on the walls. As the days heats up, the friendly touts start hussling for business. By the second day they realised we weren’t interested in a boat ride or a map of the island and left us alone. On the third day there were some new touts and we were puzzled why they were starting up again. Then we realised it was Saturday and this new batch of persistent touts were actually the school kids who hadn’t seen us on previous days as they were at school!

Like Lamu in Kenya, Ilha de Mozambique is one of those ‘go now before it changes too much’ places. It’s a Unesco World Heritage site and a big effort has been made to ensure children have reasonable schools to go to. There’s also clearly foreign investment flowing in to pave the dirt streets and restore a few of the crumbling buildings, probably to run as guest houses or cafes, or to let as holiday homes. Whilst most are in-keeping with the architecture and respect the people and atmosphere of the ilha, a few are starting to create a particularly uncomfortable gap between the dilapidated courtyards and shacks that people live in, and the ’boutique bubble’ of the hotel. Much of Ilha’s charm lies in the flaking paint on the walls, children playing football in the dusty streets, and fishermen mending their nets on the beach in front of the Church of Saint Antonio. I hope it doesn’t eventually become the Capri of the Mozambique coast……

********************

We arrived in Malawi during a time of fuel shortages and anti-government demonstrations (yep, deja vue). So we decided to leave the car and take the MV Ilala to Likoma island in the north of Lake Malawi and in fact closer to the Mozambique mainland than to that of Malawi. Over the course of a week (roughly), the Ilala stops at various points on Lake Malawi heading north from Monkey Bay and then returning the same route. When we were in Malawi many years ago it would have taken us 10 days by boat to get to Likoma. Today, it would be a mere 12 hours on the Ilala. A doddle, surely?!?

Ah, but this is Africa, and things don’t always run as expected….

The Ilala has a schedule, probably for legal reasons. In reality, arrival and departure times are unpredictable. If you have night departure, most guest houses have watchmen that will wake you up when it arrives. There’s no rush though, as it will likely only depart a few hours later. As an example, we eventually saw our 6.15am ferry on the horizon at lunchtime. We boarded around 3pm and eventually left at 8.30pm.

The arrival of the Ilala is quite an event at all of the stops. Markets spring up on the shores on ferry day and people throng the port area either to board with their cargo or just to watch the spectacle.

The Ilala probably has cargo and passenger limits too, also for legal reasons. In reality, no bundle, box or passenger will be turned away. As a result, loading and unloading takes several hours at every stop. It’s quite a sight to watch the enormous boxes filled to bursting with tiny carpenta fish, or cumbersome barrels of diesel being hauled on and off the boat. We even saw a Coke vending machine being unloaded onto the lifeboat and taken ashore!

On the second class deck where you find most locals and all the cargo there is always only a sliver of a passageway to walk down. Boxes and sacks are piled to the ceiling and people cram themselves into any tiny space they can often for journeys that last two days or more. The cramped conditions are made worse by the combined smells of dried fish and diesel, and not much ventilation.

The time taken to unload and load isn’t helped by the fact that some of the stops don’t have jetties, including our start point at Nkhotakota and end point at Likoma island. The process of getting onto the Ilala involved some combination of wading waist deep through the water and/or two leaky boats to get to the slippery wooden steps that you climb to board. You will, of course, be trying to climb these narrow, slippery steps at the same time as eight Malawians and their cargo of dried fish. When you are eventually on board, you have to squeeze down the passageway, stepping over sacks of vegetables, and find the stairs to the upper deck. It’s a bit scarier getting off as eight other Malawians with their cargo will be pushing you down the stairs into the boat below so they can get off too. And then there’s still the wading to shore……

Almost all of the foreigners opt for the first class deck. Here you’ll find a nice bar and a relatively clean deck scattered with a cargo of backpacks. You can also rent a mouldy foam mattress to lie on overnight whilst you watch the shooting stars. Ven and I had packed light and had not expected to be spending the night on board. By 8pm we were wearing everything in our packs!

We spent a couple of lovely days in Likoma, walking through the incredibly friendly and neatly kept villages and visiting the Cathedral of St Peter, built in the early 1900s and measuring 100m by 25m. Quite impressive for an island only 17 sq km! We also saw a clothes auction in the market square, where the ‘auctioneer’ called out successively lower prices for items such as T-shirts and blazers until someone made an offer. You could see people trying to make tactical decisions, waiting to get the lowest price possible but having to make a bid before someone else did! There are also beautiful baobab trees along the coastline where you can see families drying small carpenta fish on raised reed mats.

Our time in Likoma was very relaxing, but it was the chaos of the journeys there and back that was the most memorable part of the trip…..