This is the post with photos of beautiful beaches and pretty fishing villages, so if you’re reading this on a grey, rainy day in a concrete jungle, feel free to skip to the next post!

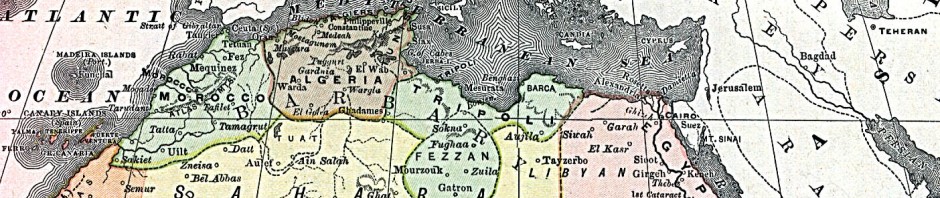

The East African coast is dominated by Swahili culture, very different from the African culture inland. The islands are especially where much of it can still be experienced. Together with beautiful beaches and good snorkelling, that’s where we wanted to head to.

The Swahili race, language and culture developed as Africans and Arabs inter-married when the trading routes were set up in the 1st century AD. By the 16th century, as trade flourished, the Europeans decided to grab a slice of the action, starting first with the Portuguese. They were defeated by the Omani sultans, but then came the European missionaries and explorers in the 1800s. The British eventually helped end the slave trade in 1873, and clearly this did no harm to their expanding interests in the area. Add to this the Indians, who originally arrived to build the Uganda Railway and who were then allowed to set up businesses, and you have a fascinating mix of cultural influences in the language, food, architecture and clothes in these traditional, largely Muslim, communities.

We took advantage of a safe place to leave our vehicle in Mombasa to go to Lamu, an island off Kenya’s coast. It’s a World Heritage site and typifies the more relaxed pace of the coastal communities.

The bus company told us it would take 6 hours to the ferry, from where it’s a short ride to the island. My general rule with any timings in Africa is to add 50%, though Ven was more certain 6-7 hours would be about right. 10 hours later we were on the overloaded ferry heading to Lamu Town….. A flight back to Mombasa was looking very tempting!

Lamu Town, the island’s main village, is like a smaller, more low key version of Zanzibar’s Stone Town – narrow streets, tightly packed with run down houses and shops with beautiful wooden doors and balconies. The hassle-factor is low and any encouragement to “come see my shop” or “buy octopus”(!) is good natured and not persistent. The latter offer was tempting but rather inconvenient given our stove was back in the car in Mombasa!

We stayed in Shela village, a 3km coastal walk away from Lamu Town. The path periodically runs out, so it’s not uncommon to see Muslim women hitch up their long cover-alls and splash through the water. In fact, people spend a lot of time walking through the water – Shela has no jetty, so if you’re being picked up or dropped off by boat you have to wade to shore!

We stayed at converted Swahili home called Banana House. Typically, many of the rooms have small windows to keep them cool, but there are large airy covered verandahs to lounge around in. I thought it was named after a shady tree that was perhaps in its garden, but instead, it’s owned by a local guy called Banana!

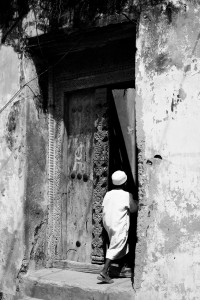

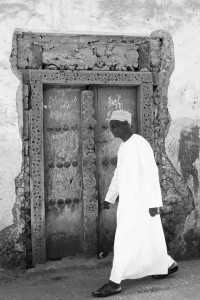

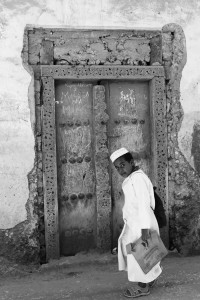

It’s lovely to wander around Shela’s narrow sandy streets and to discover a beautifully carved wooden door as you turn a corner, a traditional coral-walled house, or a tiny shop selling a few vegetables and sweets. The doors are a mix of various styles – Omani, Gujurati, Zanzibari – reflective of the melting pot of cultures that have lived on the island over the years. It is good to see that the new houses have commissioned local carpenters and carvers to carry on the tradition of the beautiful wooden doors.

It’s a conservative Muslim village and people dress relatively traditionally. The place is changing fast though as more old Swahili houses are being bought by foreigners and converted into guest houses. Fortunately though, the locals still hold onto parts of the plots of land they sell to build their own houses, and so there is still an opportunity to see local life, like fishing and shipbuilding, carrying on around you.

Lamu island has 2 trucks, both ambulances – one for people and one for donkeys. This is important as there are no other cars, and donkeys are the main form of transport, carrying everything from people to groceries to building material. And when they grow old, there is even a donkey sanctuary they can retire to.

Our next island jaunt was from Dar es Salaam in Tanzania to Mafia island. The flight to and from Mafia was great fun – a 5-seater plane and I got to sit next to the pilot on both journeys! The safety briefing was amusingly minimal – “make sure your seat belts are fastened, life vests are under your seats, enjoy the views!” And the views are indeed better than any in-flight entertainment system. There was a dual control set-up in the plane and it was very tempting to grab hold of the steering column and have a go at flying it. Fortunately for the other passengers, I resisted temptation, especially as there was a note taped to the cockpit reminding pilots that “no acrobatic manoeuvres, including spins, are approved”. Also amusing was the plane’s Garmin GPS, which felt even less sophisticated than the set up in our car, and the air conditioning unit which was little more than a tube leading out from the plane.

Mafia Airport is a small tin roofed building with a ‘waving bay’ to one side from which you can say your farewells to people in style or watch the plane come in. The ‘departure lounge’ is like someone’s living room, with a few old velour covered sofas. And the runway is a dirt track. It was lovely to be able to walk off the plane and onto the street in under 30 seconds. We were even able to walk to our guest house from the airport. The Heathrow Express is a distant memory….

Mafia island is in a marine reserve. Whilst there are small villages around this and nearby islands, the main activities are snorkelling and diving. The coral is especially beautiful. As we waited for our ‘dalla dalla’ (share taxi) under the big tree after our snorkelling trip, we watched the boatmen ferrying people and their provisions to nearby Chole island, which we had wandered around the earlier that day.

It took three visits to the Mozambique embassy in Dar to get all the relevant bits of information in order to submit our application for a visa. The process would take 5 days, so we decided to head to Zanzibar. We had both been there separately over a decade ago and had originally decided to give it a miss, fearing it had become too developed.

12 years on, there are still lots of touts along the port road in Dar trying to get a commission on your ticket purchase, and you have to have eyes in the back of your head to make sure you’re not followed into the ticket office by one of them.

Zanzibar’s heyday as a powerful city-state was between the 12th and 15th centuries as a trading post linking Arabia and Persia with India and Asia. It supplied gold, ivory and slaves, and imported spices and textiles. From the 16th century, the Portuguese, British and Omani Arabs all tried to control it and it fell into decline. Only in the 19th century did it flourish again under Omani control. After the slave trade ended, the British controlled it until its eventual independence in 1963. Just a year later, a bloody revolution ended with Zanzibar signing a unity agreement with Tanzania.

Zanzibar has its own quirky customs and immigration, even though it is still today part of Tanzania. We had to sneak past it on arrival and departure as our passports were at the Mozambique embassy. We had taken the receptionist’s phone number in case there were any problems in Zanzibar and I was ready to get them to ‘call the Ambassador’ (aka the receptionist) if they stopped us from entering!

Zanzibar has changed since the last time we were there. But interestingly, not all for the worse. Gone are the scores of touts that latch onto you on arrival. They’re still there, but far fewer and far less persistent than they used to be. Even around Stone Town, the hustlers looking for a Spice Tour commission or a guiding fee are good natured about it all and do take ‘no’ for an answer the second or third time you say it. And thankfully the quality of food available has greatly improved – we were amazed that the street food stalls in the gardens at night now even have menus and prices in English! The melting pot that is Swahili culture may have been taken too far though when you see a ‘fusion Indian’ restaurant called Silk Route with a Masaai warrior standing guard outside!

Sadly though, there are far fewer tiny tailor shops than we remember – ‘mom and pop’ businesses who would take your measurements and have your shirts and sarongs ready for you the next day in whatever fabric you chose. And there are virtually no artisans working in their tiny, poorly lit workshops any more. Instead, there are larger brightly lit souvenir stores selling sarongs and satchels you might see in Thailand, and mass produced ‘hand carved wooden African masks’ made in …. China?

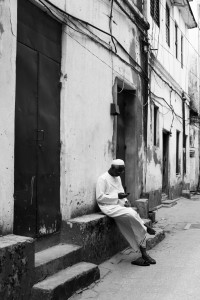

Wander deeper into the heart of Stone Town though, through the labyrinth of streets with peeling plaster walls, this is where people live – behind beautifully carved wooden doors, a little worn at the edges.

Early morning, the light catches the just the tops of the buildings. By the time the sides of the buildings are lit, kids have started running through the streets on their way to school, dressed in traditional Muslim uniforms, boys with white caps and girls with head scarves. By mid-morning, there’s more people on the street and the sounds of the ‘Zanizi Top 20’ are playing on the radios in the stores. You can catch glimpses of courtyard life through the occasional open door, with washing being hung and food being prepared sitting on the floor, and cooked in steel saucepans on coals. Tiny stores selling sweets and washing powder open their shuttered windows and there’s the occasional street stall selling skewers of meat or bowls of soup.

Things quieten down again in the heat of the day, but by mid afternoon the kids are back on the streets, this time hurtling around corners on their bicycles. Or somersaulting off the wall into the high tide water by the fishing boats. By 5pm it’s time to stake out your sunset spot. The Africa House Hotel used to be the classic spot for backpackers, so that’s where we headed. The plastic chairs and ‘beers in a bucket’ have been replaced by beautifully carved wooden chairs with cushions, and a colonial style wooden bar. It’s still a nice spot to watch the dhows sailing out on sunset cruises and a big red African sun in the background.

Reluctantly we tore ourselves away from Stone Town and headed to Matemwe beach on the eastern shore of Zanzibar. We didn’t quite know where Mohamed’s place was, but the dalla dalla (share taxi) ticket collector did, and we were dropped off on a dusty road in the middle of a village and ushered off into its depths.

Mohamed is a local guy who used to work in a fancy foreign owned hotel. He bravely decided that he would strike out on his own and over a number of years saved enough money to buy a small plot of land on Matemwe beach. In Zanzibar’s efforts to upscale, his place is as close to ‘a beach hut on the beach’ as you’re going to get these days. With just 4 thatch roofed bungalows, a restaurant and beach bar, and with upmarket hotels and private villas for neighbours, he’s flying the backpacker flag remarkably well. With fresh seafood always available, his tiny kitchen turns out a particularly delicious ‘Fish al Yusria’, with a sauce made with ginger, garlic, fresh tomatoes, tomato paste and coconut milk. He did well to buy his plot of land many years ago as the Zanzibar coastline is prime real estate now with foreigners trying to buy land to build hotels along its beautiful beaches. Despite being offered big bucks by various people, he’s hanging in there, and it’s lovely to see a locally owned business doing well.

Back in Dar es Salaam, and armed with our Mozambique visa, we headed south through Tanzania, stopping off at Kilwa Kisiwani, (Kilwa on the Island). The island used to be at the centre of trading routes linking the gold fields in Zimbabwe to India, China and Persia. And was later a trade route for slaves into Mauritius, Reunion and Comoros. The ruins of the mosques and other buildings date from the 12th to 16th centuries and are now a Unesco World Heritage Site. They have an atmospheric setting and it’s lovely walking through the small fishing village to get to them.